Geidō: The 3 Phases of Mastery

Bruce Lee, Sushi Chefs, and the Path to Authentic Work

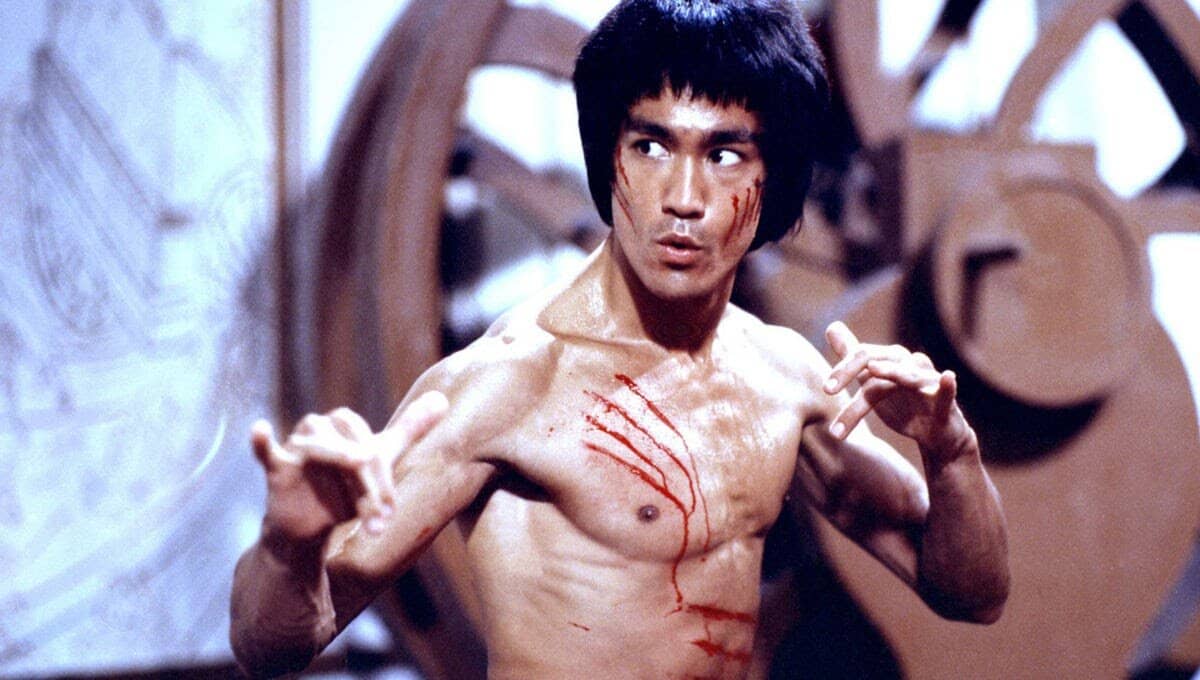

In 1953, at the age of 13, Bruce Lee was introduced to Wing Chun master Ip Man by a friend after getting into frequent street fights in Hong Kong. Bruce wanted discipline and control, and Wing Chun promised both. He was accepted into Ip Man’s school despite initial resistance from other students due to his mixed heritage.

Bruce didn’t start out flashy. He spent long hours drilling footwork and throwing the same punch over and over under the watch of Ip Man’s senior students. While Ip Man rarely taught Lee directly, he supervised his development and encouraged him to train with his top disciple, Wong Shun Leung.

For several years, Bruce committed to mastering the fundamentals. He trained relentlessly. Not to show off—but to understand. To build something solid.

That was his world before everything changed.

As Bruce grew older, his world expanded. He began exploring beyond Wing Chun. He sparred with boxers. Studied fencing. Imitated Muhammad Ali’s footwork. Read books on philosophy and psychology. He stopped treating martial arts as fixed techniques and started treating it as a living system.

Eventually, he broke away from every style, including the one that shaped him. He created something of his own. Not a new technique, but a new way. “I don’t believe in styles,” Bruce Lee said. “Styles separate men. It’s a process of continuing growth.”

His most famous quote captures the transformation:

Before I learned the art, a punch was just a punch. After I learned the art, a punch was no longer just a punch. Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch.

It sounds poetic. But it’s also practical. Because mastery always follows this kind of arc, where what once looked simple becomes complex, then becomes simple again.

The Japanese Path of Mastery

In Japan, this idea has a name: Geidō (芸道) — “the way of art.”

It’s not limited to martial arts. It shows up in calligraphy, tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and even in how sushi chefs train.

In traditional apprenticeships, a student might spend months—sometimes years—just watching. No tasks. No shortcuts. Just observing the master’s work with full attention.

A sushi apprentice, for example, might wash rice for an entire year before they’re even allowed to touch a knife. They learn how to rinse and steam each grain to perfection, adjusting for subtle changes in temperature and humidity. After rice, they move on to grating wasabi, preparing tamago (egg), and perfecting the hand movements for shaping nigiri—often without fish.

Only after mastering these seemingly simple steps are they allowed to work with raw fish, and eventually, serve customers. The journey from apprentice to itamae (head chef) can take over a decade.

It’s a process built on patience, humility, and total immersion. Because in Geidō, mastery isn’t a destination. It’s a process of transformation through three phases:

Phase 1: Shu (守) — Commitment

This is the phase where you follow the rules.

You don’t question the form. You don’t try to stand out. You show up. You repeat. You sweat the basics.

In Shu, you build discipline through imitation. You surrender to the process so that it becomes part of you. Think of Bruce Lee in his early years, drilling punches under Ip Man’s gaze.

Phase 2: Ha (破) — Mimicry and breakthrough

This is where you begin to test the form.

You experiment. You explore new techniques. You adapt the rules based on your own context and experience. It’s no longer just about obedience—it’s about insight. You start thinking for yourself.

Phase 3: Ri (離) — Expression and freedom

This is the stage of transcendence.

You’re no longer bound by rules. You’ve internalized the art so deeply that your actions flow naturally. Your work becomes an extension of who you are.

This isn’t rebellion—it’s return. A full-circle moment where the punch is just a punch again, but now, with power behind the simplicity.

The danger is trying to skip ahead.

Most people want to jump straight to Ri—to expression—without putting in the reps of Shu or the discovery of Ha. But true freedom comes from structure. From tension. From walking the path, not bypassing it.

So, how do you walk it?

How to Practice Geidō in Your Work

Here’s how to apply this to your craft—whether you’re building a business, writing, designing, or leading a team.

1. Pick a craft and commit

Most people stay in dabble mode. A bit of writing here. A bit of marketing there. A bit of leadership when they’re forced into it. That’s fine at the start. But eventually, you have to choose.

Pick one craft to commit to for the next 12–18 months. Make it your focus. Build your reps. Ask yourself: “What am I willing to be bad at—long enough to get good?”

Perhaps it’s writing better, or managing people, or mastering your business’s positioning. It's the Rule of 100 from the book Million Dollar Weekend by Noah Kagan.

Whatever it is, decide. Then go deep.

2. Choose your models wisely

In the beginning, your job isn’t to reinvent the wheel. It’s to understand how the wheel works.

That’s why the first step isn’t originality. It’s mimicry. But not blind copying—intentional study. Pick your models carefully.

- If you’re a writer, study Paul Graham’s essays or William Zinsser’s chapters. Pay attention to how they open loops, build arguments, and land their points.

- If you’re a marketer, dissect how brands like Apple create product desire. How Nike tells stories with almost no words.

- If you’re a founder, look at how Daniel Ek scaled Spotify through relentless focus or how Yvon Chouinard built Patagonia by embedding values into every decision. Read their interviews. Watch their talks. Understand the thinking behind their actions.

This isn’t about imitation for the sake of it. It’s about fluency. The better your inputs, the sharper your instincts become when it’s time to build your own voice.

3. Don’t rush expression

Everyone wants to be different. But being different without being good is just being loud. Expression comes after fluency, not before.

You don’t “find your voice” by searching for it. You develop it by practicing until it emerges on its own.

If you want to explore your style, create a side project. A sandbox. Somewhere to play without pressure. But for your main craft, stay in mimicry until you’ve earned the right to break the rules.

4. Borrow from other domains

Some breakthroughs happen not by going deeper into your craft, but by stepping outside of it.

Bruce Lee studied boxing and fencing to improve his martial arts. Writers study jazz to understand rhythm. Entrepreneurs study military history to learn about strategy and leadership under pressure.

When you hit a wall, look sideways.

- What can designers learn from architecture?

- What can marketers learn from stand-up comedy?

- What can leaders learn from sports coaches?

Pulling insights from other disciplines doesn’t dilute your craft—it sharpens it. Because real originality often lives in the intersection.

5. Return to the basics

Geidō isn’t linear. You don’t go from Shu to Ha to Ri once and you’re done. Every time you level up or switch arenas, you start the cycle again.

Even Bruce Lee returned to the fundamentals. Even Michelin-starred chefs still obsess over rice and knives.

The same goes for other areas of life:

- In productivity, you might explore new tools or systems, but eventually, you’ll come back to simple things that work, like a clear to-do list and focused blocks of time.

- In personal finance, you might experiment with investment strategies or tax optimization, but it always returns to the basics: spend less than you earn, automate your savings, and avoid dumb risks.

- In health and fitness, the flashiest biohacks don’t matter if you’re not sleeping well or drinking enough water.

Whatever stage you’re in, keep circling back. That’s where depth lives.

Mastery Is a Quiet Transformation

It doesn’t come from a course or a hack.

It comes from time. From repetition. From humility.

In a world that rewards speed and novelty, mastery is your edge—because few are willing to walk the long path. So ask yourself:

What phase am I really in—Shu, Ha, or Ri?

You can’t fake this.

But if you honor the process, your voice will emerge. And when it does, it won’t just sound different. It’ll feel true.